My answer to a casual question triggered the beginning of the end of my career shooting pictures.

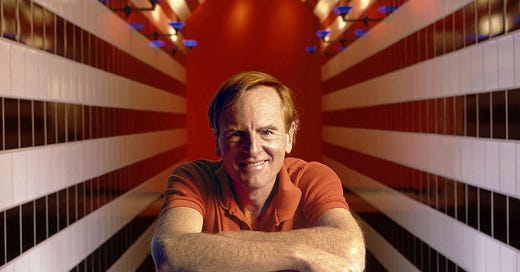

Jeff Cohen had one of the most enviable business cards in the world: Photo Editor, Playboy. I’m sure he never paid for drinks. Jeff assigned me to photograph Apple CEO John Sculley, in 1987, for the September “Interview” section of the magazine. (Clearly, that was the only reason readers were expected to buy it.) Two years since Steve Jobs left the company, Sculley’s star shone brightly in the corporate firmament. This was my first time to meet him.

Sculley asked me, “How do you like the Macintosh?” He was naturally curious because this most personal of personal computers was designed to appeal to creative types like me. It did. I was an early adopter — first on my block, in 1984, to buy the original 128K version — and a serial upgrader: the 512K Mac Plus; the SE; the SE/30; the SE FDHD with two built-in floppy drives; and the last version of the little beige box, the Mac Classic. But — if I can paraphrase a well worn line — the first Mac* had me at “Hello,” which it actually spoke out loud and displayed as text on its little black-and-white screen when Steve Jobs turned it on in public for the first time. I was now three years into my enthusiastic engagement with this unprecedented machine. I answered Sculley’s question candidly and without hesitation: “It’s a nice toy, fun to use,” I said, “but I wish it could help me run my business.” It was basically a techie typewriter; cute, but with little more than a built-in Rolodex, primitive email, and rudimentary graphical capabilities. My garage-door opener, today, has more computing power those early Macs.*

Footnotes/Asides

* Contrary to popular myth, Jobs was not fired. He resigned at the behest of Apple’s board of directors. Although he’d held the title of chairman, he was essentially the product manager for the Macintosh project; Sculley ran the company. To be sure, Sculley did not stand up for Jobs when Jobs was butting heads with the board. But Sculley’s accomplishments as Apple’s leader for ten years were eclipsed by the apocryphal story that he personally gave Jobs the heave-ho. And because Sculley was recruited by Jobs in the first place, he bears a scarlet letter, an ignominious malediction from Jobs’s acolytes. Jobs famously asked Sculley, then PepsiCo’s president, “Do you want to sell sugar water for the rest of your life, or come join me and change the world?”

* Originally named by Jeff Raskin, its lead project engineer, after his favorite apple, the McIntosh, the name got tweaked to Macintosh for legal reasons: Another company in the electronics business had already trademarked McIntosh.

* It’s hard to grok how little memory and storage space they had. I paid $3K for a 10 megabyte external hard drive, in 1986, with a footprint that fit flush underneath my Mac. That’s more than $7K in today’s currency for not even close to 1 gigabyte of storage; hardly enough to download an iPhone app. A 1 terabyte thumb drive is 1 thousand gigabytes, or 1 million megabytes, or 1 billion kilobytes, or 1 trillion bytes and can be had for peanuts at a local pharmacy or big-box store. Compare those numbers to the risible 128 kilobytes in the Mac’s first operating system. Holy WYSIWYG!

People still wrote letters. For email we’re talkin’ “baud rates” on a dial-up land-line to get on AOL, Prodigy, CompuServe, or Alta Vista. The movie, “You’ve Got Mail,” was still five years out, when a recorded voice that would utter that timeworn phrase would be as familiar as Siri is today. The World Wide Web wasn’t yet a twinkle in Tim Berners-Lee’s eye.

I remember a story, no less entertaining, even if it, too, is a bit dubious, about an elderly woman who was shown a Macintosh for the first time. She marveled at its remarkable ability to let her type on a keyboard and see text on a screen. But she asked, “What does the foot pedal do?” If you don’t understand, you’ve never seen a sewing machine.

Ididn’t mean to throw John a curveball. I think he was surprised I didn’t simply say, It’s great! So, he pushed back, “Why don’t you create some software, if you think you know what it needs?” I told him I was an artist, not an engineer; and we laughed it off. I’m certain John thought nothing more about it, and the shoot went along without a hitch. Apparently, I made a good impression because the Playboy shoot led to a subsequent meeting with Apple’s design director, Clement Mok, and six years of work directly for Apple. Mok had been standing close by while I was photographing Sculley.

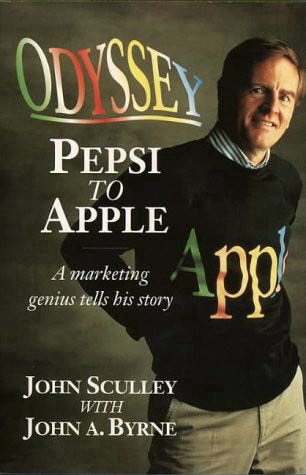

Not only did the company become a steady client but Sculley tapped me for personal work, too, including the dust jacket for his autobiography, Odyssey, published in 1988. Later that same year, I made this portrait of him posing with a Mac in the corridor of a building on the Apple campus that led to a Cray supercomputer once used to design in-house circuitboards. There, too, we got into a discussion about Macintosh software and its deficiencies. Sculley, once again, challenged me to create something. And again, it was a conversational throwaway. But this time he struck a nerve, igniting neurons throughout my brain that didn’t stop firing for years to come.

Here’s the deal. No one picks up a camera just for the sake of starting a small business. Rather, enthusiasts hope to support their art, and that their art will, in turn, support an artist’s lifestyle. It’s all very tidy in theory. But a well rounded photographer can’t roll downhill when it comes to remaining solvent. It’s tough trying to navigate the world of business and shoot pictures at the same time. I’ve never met a photographer who wasn’t three or four days into one job or another and six weeks behind on invoicing, wondering why cash flow made sucking sounds. And pricing! The more accomplished among us could only stick a wet finger in the air to see which way the wind blew. It was all guesswork. Nonetheless, my career was taking off like a Saturn rocket. I was one of the lucky few to be busy shooting photo assignments all over the world. Some of them, including for Apple, were in Silicon Valley where I clearly heard the loudest buzz: “business automation.” I figured,if I could do a brain dump of everything I knew about the business side of photography into an easy-to-use software package, I could do a great service for my profession and make a lot of money to boot. Photographers needed a kind of GPS-guided robot to take them by the hand and lead them step-by-step from taking pictures to making money. We all wanted to spend more time behind a camera and less time behind a desk. And we had to protect ourselves from the mindset of a corporate-clientele that brutally exploited a pervasive ignorance, theirs and ours, about the economic value of photography as intellectual property; that it is licensed butrarelyever sold. We weretrying to be professional, profitable, and to build individual wealth. It wasn’t going very well.

Ifyou hang around tech long enough, you can’t help but get some of it on you. One morning in the spring of 1991, with those neurons Sculley ignited with an inadvertent dare still going off like fireworks in my head, even in my dreams, I woke up on the wrong side of bed. I was suddenly obsessed with learning how to “program” software, dead set to create a business automation solution for photographers.* I already owned the latest and greatest computers: a Macintosh IIsi and a Mac Quadra 900. I even had a Macintosh Portable, the first battery-powered Apple computer. Weighing in at 16 pounds, however, its name was equivocal. But portability be damned! I sequestered myself at home in Sausalito and, for two years, sweated out algorithms and formulas and relational databases, as well as a graphical user interface (GUI) to create hundreds of screen layouts. I pored over database-design instruction manuals. I got some help with graphic design issues from Clement Mok who had left Apple to start his own practice. I was visited by friends who were concerned about my disappearance from the social scene. They brought food (wellness checks maybe). Perhaps they were conscious of the stereotype: a Cheetos munching, Mountain Dew swilling software dweeb. But I, too, dreaded becoming that guy, a consequence of dogged isolation in the company of computers; I took care of my health. I found I could solve punishing programming problems in my head while I ran five miles, a thousand vertical feet down Bobcat Trail to Cronkite Beach and back up, or mountain biked through the Marin Headlands, up and down Mt. Tam. I already had a name for my creation: PhotoByte.

I was in dangerous territory financially, spending more time on PhotoByte than shooting pictures for clients when, in 1992, I crossed a bridge and burned it. I was hoodwinked by self-revelation during a photoshoot with another tech CEO, Hewlett-Packard’s John Young. About to retire, this was his swan song interview for Forbes, or maybe Fortune. Like his competitor, John Sculley, Young was personable and inquisitive, even curious about photography. Young wanted to know who and what I liked to shoot. I told him how, oddly enough, I enjoyed photography more than I enjoyed being a photographer, that I liked looking at what I (and other photographers) had done more than actually doing it. Something clicked, not my shutter. I wanted to tell him about PhotoByte. I felt like boasting that, if everything went right, someone would be photographing me as the CEO of my own company. He encouraged me. It was a time before Silicon Valley Fever had completely infected the national psyche; before the popularization of startups as a thing; before the ethos of “two guys in a garage.”*

Hewlett-Packard (H-P Inc.) is the epitome of the two-guys-in-a-garage meme. William Hewlett and David Packard are the originals, the real deal, the first “two guys in a garage,” quite literally, who started their fledgling company in a garage adjacent to one partner’s house in what was hardly known, yet, as Silicon Valley; although some might take that argument all the way back to Wilbur and Orville Wright and their little workshop in Dayton, Ohio.

Another year rushed by. I finished what, today in Startup Land, is called an MVP or minimum viable product. As soon as I got the chance, I told Sculley about it.

“John, do you remember that conversation we had a couple of years ago about the Mac, how I wished it could help me run my business?”

“Yes,” he said.

“Well, I did it. I created a tool that automates all the business-management stuff photographers hate and don’t have time to do.”

I think John realized that, if I really had such a thing, it would help sell Macs. Apple was in dire need of software solutions to bundle with Macs, to sell to freelance professionals. The PC powerhouse alliance of IBM and Microsoft was kicking Apple’s ass in the corporate marketplace. But because the Mac was easier and more fun to use, creatives gave it all their attention. I think it’s safe to say that 95% of all photographers were Macs, not PCs. Certainly, the Mac dominated the commercial illustration and design industries, too. Early versions of Photoshop and various flavors of “desktop publishing” software had taken center stage. But these were not back-office business tools; they were creativity tools. The sexy science of digital imaging was going great guns, but creatives were keenly aware of the indifference paid to the development of invoicing and administrative software tailored to their needs. Business software on both Macs and PCs was generic and didn’t address the arcane workflows peculiar to freelancers who were themselves in business. With that in mind, and — who knows? — maybe John was just humoring me, he set up a demo with Apple’s software development team.

Sculley did not attend the demo. But a half dozen business-development big shots were waiting for me in a big glass Apple conference room— like being in a fish bowl — at One Infinite Loop. I plugged into a projector and ran through the features of PhotoByte. It took about forty-five nerve-wracking minutes. I was shaking in my shoes. When I finished, the team’s lead came over to me, shook my hand, patted me on the back, and said, “How’d you like to run a $10M company?”

As soon as I picked my jaw up off the floor, I asked him, “When do we start?” By implication, Apple would either invest in a new company led by me to further develop and market PhotoByte — terms and equity to be determined, or they would make an offer to buy PhotoByte. But to keep my story concise, I’ll just say that, metaphorically speaking, in the time it took to drive home, from Cupertino to Sausalito, the man from PepsiCo who took up Steve Jobs’s famous “sugar water” challenge lost his fizz at Apple. John Sculley got fired; or, rather, he was asked to step down as CEO by Apple’s board of directors. It was June, 1993. He remained as board chairman until October, then left for good with a delicious severance package. I think he was undermined by two failed initiatives, Apple’s introduction of a personal digital assistant, the Newton, and the company’s quixotic copyright infringement lawsuit against Microsoft and Hewlett-Packard over the exclusive right to proffer a visual graphical user interface on their computers.

There was little chance of my pursuing a deal with Apple at this point. The company was in a tizzy. I didn’t know what my options were, anyway, ignorant as I was about the rules for playing in the corporate-capitalist sandbox. I wasn’t giving up, though. Knowing nothing about the investor community of angels and venture capitalists, I liquidated a real estate asset and tapped into my savings to recruit a crackerjack marketing executive and a boilerroom full of cold callers in Coeur d’Alene, Idaho. We sold shrink-wrapped software to photographers at five hundred bucks a pop. But I realized, two years in, that dialing for dollars and pitching to photographers at trade shows was not what I gave up a glamorous career to do. It was no way to make one’s dent in the cosmos. I started thinking about getting investors on board, and learning how to do it. I was still augmenting my income, in bits and pieces, by continuing to take photo assignments.

In the mid-90s, an upstart company called Getty Images and another stock photo company called Corbis (the latter wholly owned by Bill Gates) were competitively and greedily rolling up fragmented photo agencies around the world into one big ball — well, two big balls — of revenue. As private equity enterprises, they were altogether another kind of investor: financiers taking quick profits, with inimical regard for existing customers and market norms. With no hands-on photo business experience, they didn’t so much disrupt the industry as simply buy it. They turned it into a consumer-facing retail business, providing cheap pictures to fill up an exponentially increasing number of “newfangled” websites but ignoring the larger and more lucrative licensing transactions typified by major corporate brands and media companies doing business with the photographers who serve their needs. For the sake of brevity, I’ll just say that Corbis ultimately lost its bite, but Getty, now the 800lb. gorilla that ate everything in sight, suffers from chronic indigestion. The Commercial Photo marketplace is vulnerable, now, to real disruption than it was in the 90s. (That’s another story.)

Then, as now, I recognized a way to make an end run around Getty Images. I could hone a competitive edge to consolidate photographers and their work on PhotoByte’s proprietary platform (a new kind of online marketplace) while optimizing their income and helping them better serve their own clients. To put it simply, the plan was: Once the number of PhotoByte users reached critical mass, I’d flip a (metaphorical) switch to empower them to license their exclusive premium photos to publishers at fair market prices. (These are photographs in continuous production to this day, but still invisible online.) I pitched two bankers I’d photographed years earlier for Fortune. They gave me a seed round of funding. They also introduced me to a man who had recently retired from Intuit, the self-professed Father of Quickbooks, who was looking for a new opportunity.

Because of his bona fides in Silly Con Valley, I took on Daddy Quickbooks as the CEO of my company, which I called Vertex Software. With my limited experience in corporate dynamics, I thought he’d be better suited to manage what I expected to become a very large enterprise. It was the biggest mistake I’ve ever made. I remained as chairman with a huge hunk of stock, but, if you’re not the CEO who controls the vision of the company, you’re quickly marginalized by the guy who is. He insinuated himself as my cofounder and cajoled a restructuring of the company, now called Exactly Vertical Inc. I’ll give him credit, though, for being instrumental in our raising more than $7M in venture-capital funding. But he spent it all within a year on boondoggles. He had no comprehension of the market. And he was so full of himself, there wasn’t enough room in his head for an original thought. Worst of all, as CEO, he had the power to change our business model: Once the number of photographers using PhotoByte (now called Exactly for Photographers) reached critical mass, we — he — flipped a switch to sell them film on the Internet. (Yeah, I know.) My hair was on fire. I was jumping up and down until, by the time the board of directors realized this fool didn’t know his ass from his elbow, it was impossible to raise another round of funding. It was the year 2000, and the dotcom bubble had burst.

Imade a solemn vow to the thousands of photographers who relied on PhotoByte that it would not go away. I sold my house in Marin and almost every stick of furniture in it to buy back the intellectual property I created (the PhotoByte software) from the company I founded, now bankrupt, and then to pay the lawyers. I last upgraded PhotoByte in 2004 and made it available, to download for free, on my personal website. Seventy thousand photographers did. Everything else I owned, except for my motorcycle and my truck, was put into storage: my career archive of film, my books, my sheet music, my clarinets, and a cherished desk. I couldn’t go back to shooting for a living because my network of clients had all moved on, and the transition from film to digital was in full swing; I’d have had to buy tens of thousands of dollars of new digital camera gear. That was pretty much impossible; I’d lost my shirt. For several years, until after my Art of the Chopper book publishing deal, and even after that for awhile, I lived by couch surfing, housesitting, and renting rooms. Not fun. Depressing. Nonetheless, I was waiting for the planets to realign. In the meantime, as computer operating systems modernized, photographers continued to use PhotoByte; though they had to resort to keeping it on portable USB drives and dedicated laptops running older operating systems. Ultimately, PhotoByte could not keep up. Today, it’s functionally obsolete.

Sculley moved to New York. I visited him there one day in the early 2000s. As I remember, he and his brother founded an investment company that specialized in high-tech medical devices. He had no further interest in PhotoByte. My visit was social with, maybe, a half-hearted pitch thrown in. I wasn’t very good at pitching in those days, anyway. I didn’t even have a deck. One day, though, I hope to jumpstart the original business plan and reinvent the business of photography. Commercial Photo, an essential multibillion-dollar market, is one of the few worldwide that’s still run on paper in the 21st century. Revenue is fragmented. Workflow is offline. Quality is undermined. Intellectual property is unprotected. Sellers and buyers alike, are underserved. But today’s technology makes the vision of an efficient and productive, online and data-driven Commercial Photo marketplace more viable than ever before. Wish me luck.

Tom Zimberoff is an accomplished commercial photographer, author, and photojournalist whose photographs have appeared on the covers of Time, Fortune, Money, People, and numerous other magazines.