Super-sonic-hero

My Photographic Portrait of Chuck Yeager

By Tom Zimberoff

Editor’s note: this short memoir by Tom Zimberoff was first published in 2018. We’re republishing it today, due to the passing of the legendary pilot, General Chuck Yeager.

Part One

My sister Carla’s late husband, Chuck Berman, a generation older than I am, was a WWII veteran of the US Army Air Forces. He enlisted at 17 after Pearl Harbor, became a junior officer and bombardier in a Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress at 19, and earned a Purple Heart dodging Zeros over the Pacific. After the war, then college, he got a job as an engineer at North American Aviation, the company that built the P-51 Mustang flown in combat by American aces like Chuck Yeager to escort those big bombers (albeit Yeager fought in Europe). North American also built the X-15 (X for experimental flight) in the postwar era for the Air Force and NASA. It was the first aircraft to breach the exosphere at the cusp of what we used to call “outer space.” When I was 11 my big brother-in-law brought me some autographed 8x10 glossies of test pilots who flew the X-15, including Neil Armstrong. Yeager didn’t fly that bird but he pioneered the X-plane program and, with the X-1, became the first pilot — the first anything alive — to travel faster than the speed of sound. As a kid, I worshiped those guys. Still do. My brother-in-law never brought me a fan photo of Chuck Yeager. But since I grew up to be a photojournalist, the chance came along to create one for myself.

Incidentally, I was proud of my brother Buzz, too, who enlisted in the Air Force during the Korean War when I was an infant. He was a radar technician stationed in the snowy mountains of Japan.

Because I sometimes shot photo stories with a military theme for magazines it was good business to keep touch with the public affairs officers representing each branch of the armed services. On a visit to the jointPAO in Los Angeles, I struck up a conversation with Army Lt. Col. Jim Channon about The Right Stuff, Tom Wolfe’s 1979 best-seller chronicling the epic story of America’s military test pilots and the canonization of NASA’s first astronauts. Chuck Yeager was a prominent character in the book, and he was portrayed by actor Sam Shepard in a 1983 movie adaptation that was in wide release at the time and top of mind. (It would win four Oscars the next year.) I mused out loud how cool it would be to meet the legendary Chuck Yeager in person — even better to photograph him. It was just a conversational aside. But my Army interlocutor pushed a Rolodex across his desk, like shoving a stack of poker chips into a high-stakes pot. “Call him,” he said.

I was staring at Chuck Yeager’s home telephone number. But Yeager was Air Force. Was this a dare from an Army guy? A bluff? I pondered, just for a moment, if I should play my hand or fold. I picked up Channon’s phone, got an outside line, and dialed.

One ring. Without so much as a hello, the bark of man who would brook no nonsense resounded in my ear: “YEAGER.” Oh shit! The most famous test pilot in the world was on the other end of the line, a man who might be careening wing over wing, spinning like a drill bit, and yet reporting his fearsome predicament in real time with unflappable composure over a staticky radio while struggling to keep his obdurate airplane from augering into the earth. Every pilot who ever flew a jet into a tight squeeze has learned to channel the imperturbable West Virginia drawl epitomized by Chuck Yeager, whether on a mic with a military ground crew or trying to soothe anxious airline passengers through a bumpy ride; calm is contagious: Uh, howdy folks. This is your captain speaking. We got a lil ol’ red light come on up here . . . Hearing the real deal utter just two syllables — his name — hit me like the double thunderclap of a sonic boom. It took me an awkward moment to state my own name and a reason for interrupting this man’s day. I must have made sense, though, because he agreed to meet me. He made no promises, though; he was just going to check me out. I’d be playing it like a pitch to a magazine photo editor, showing off my portfolio. Regrettably, I had to send it with my rep, Neal Grossman, to meet him because I was committed to a job on the day Yeager was available. But Neal sealed the deal. Yeager agreed to pose a few weeks later in Barstow, a California town northeast of Los Angeles in the Mojave desert where he was already booked on camera for a TV commercial. As far as he was concerned, my request made it easy for him; a twofer.

Yeager was 60 years old in 1983, a retired Air Force brigadier general. His recent public renown, thanks to the book and the movie, only underscored his real-life stature as a record-shattering aviator. He became sought after for corporate speaking engagements and commercial endorsements, flying high as a spokesman for products like Coca-Cola and Rolex. But long before his fame went supersonic, he was celebrated by aviation buffs and historians as a World War II combat hero.

Yeager enlisted in the Army as an 18-year-old private and rose through the ranks, from mechanics pool to fighter pilot. Shot down over France by the Luftwaffe, the then twenty-year-old lieutenant parachuted into hostile territory but evaded capture. He was rescued by the French Maquis, La Résistance. He helped them sabotage Nazi fortifications before humping his way over the Pyrenees Mountains on foot into officially neutral Spain. He carried along another American officer who’d been gravely wounded, saving that man’s life. Eventually, he made contact with an American consul in Gibraltar and returned to his squadron in England.

Yeager rejoined aerial combat after, first, cutting through some military-intelligence red tape, an oxymoron that almost kept him stuck on the ground. Some officers thought his contact with the Maquis made him a security risk because it was claimed he could give them away to the Gestapo if he got shot down again and captured. The matter got kicked all the way up to the Supreme Allied Commander, General Eisenhower, who ruled that Yeager should continue flying. Back in the cockpit, he became America’s first “ace in a day,” scoring five shoot-downs on a single mission. By the end of the war his decorations included two Silver Stars, two Legion of Merits, three Distinguished Flying Crosses, a Bronze Star, and a Purple Heart. One of his kills was all the more remarkable because he flew his propeller-driven P-51 against a faster and better armed Messerschmidt 262, the first jet to fly in combat.

Still an active pilot, 38 years after the war, Yeager flew to Barstow in a magnificently restored P-51, a replica of the plane he flew in 1944; convincing from its nose art to the twelve little swastikas (“kill flags”) painted on its sides to represent the Nazi planes he shot down. It was going to be featured in the General Motors spot he was filming that day when we met for the first time in person.

I was over the moon to see a P-51 parked on the apron at Barstow’s civil aviation airport and to be able to use it in my photographs. It was inspiring to watch the general march up to that warbird, gleaming under the desert sun, looking sharp as a propeller blade himself in a green flight suit embellished with an Ad Inexplorata squadron patch (i.e., Into the Unknown). Taller than most fighter jockeys, at 6’1”, his close-cropped silvery hair, sparse on top, was covered by a blue garrison cap with white piping and a single silver star up front.

After the TV commercial wrapped, then for the rest of the afternoon, I had Yeager and the Mustang to myself. In between camera set-ups I was regaled by the world’s foremost living aviator (astronaut Neil Armstrong notwithstanding) with firsthand accounts of the daring exploits I had read about in The Right Stuff and seen dramatized on the big screen. I’m sure General Yeager was tired of straightening out the apocryphal twists and turns of other peoples’ artistic license. But he could reel out his own tellings of those tales right on cue, always eager to please. Fliers will always talk about flying. And let it be said that Italians ain’t got nothin’ on fliers when it comes to embellishing a conversation with their hands; gesticulating a wing’s “angle of attack,” for instance, or the ever-changing positions of one airplane relative to another, trying to wax the other guy’s tail in a dogfight (i.e., lined up in his gunsight at 6 o’clock, right behind him). When not engaged in oneupmanship with their peers, they’re entertained by the envy in the eyes of wannabes, like me. Yeager led off with the biggest story of them all.

The first supersonic flight occurred on Tuesday, October 14, in 1947, high above the Mojave desert. It must have been all the more astounding to those who knew about it contemporaneously because, only a hundred or so years earlier, when travel by steam locomotive was still catching on, pundits warned that going faster than a horse would suck the wind out of your lungs and kill you. Civil War veterans were still alive in 1947. The Wright Brothers flew their flimsy spruce-and-muslin contraption at Kitty Hawk only forty-three years earlier. Lucky Lindy conquered the Atlantic only twenty years earlier. It had been less than a month since the creation of the United States Air Force as a separate military service. Ultimately, Charles Elwood Yeager from some holler in West Virginia, now a 24-year-old Air Force captain, sat crammed inside the steampunk cockpit of USAF aircraft #46–062, the Bell X-1, itself clasped in the talons of a sixty-five-ton B-29 Superfortress bomber flying nearly five miles above the earth at 400mph. He expected no fee, no six-figure incentive like that already demanded by other less-experienced civilian daredevils. Yeager was the only pilot willing to take on this death-defying challenge as a matter of duty, with no greater reward than a feather in his cap plus his meager military paycheck.

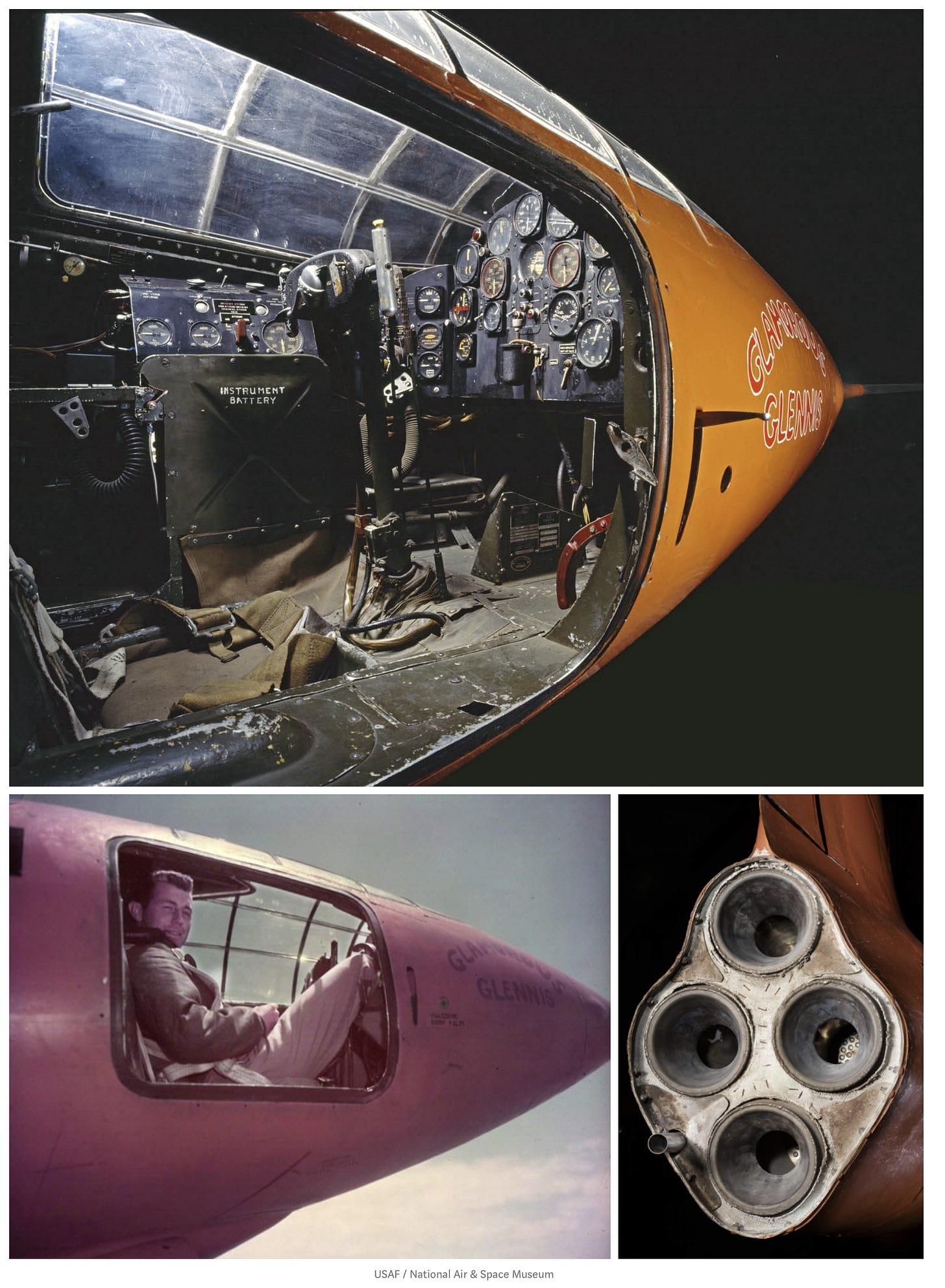

The X-1 was a manned missile painted in-your-eye International Orange, the same color as the Golden Gate Bridge, and stenciled with nose art that read Glamorous Glennis, atribute to the young pilot’s wife. It was deliberately shaped like a rifle bullet with wings, built to withstand eighteen times the force of gravity. It was about to be drop-kicked in midair, a rocket-powered kick in the ass, but not altogether unlike how the A-bombs were let loose by B-29s over Hiroshima and Nagasaki only three years earlier. This time a man was inside the bomb; so far merely along for the ride.

Captain Yeager ran through his final instrument checklist. He sat bundled in a leather jacket worn over his flight suit with his back against a giant thermos filled with 8,000 pounds of cryogenic liquid gas, a mixture of oxygen and alcohol, insulated but bleeding chill at minus 297º Fahrenheit. The windshield fogged up. His view was obscured, anyway, because the little craft was tucked halfway up inside the B-29’s dark bomb bay. He performed a final radio check then steadied his feet on the rudder pedals and his hands on the yoke, staring at a maze of dials and, in particular, four toggle switches.

Word crackled through the earphones strapped over his makeshift leather football helmet that the drop was imminent. “Roger,” responded Yeager into his mic to the mother ship. The Superfortress went into a dive to pick up speed. He listened for the countdown: ten, nine, eight, seven. . . Release! For a split second Yeager was blinded by the abrupt brilliance of the sky. But with hardly enough time to feel his stomach rise into his throat during free-fall, he flipped those switches.

Immediately, the four chambers of a Reaction Motors XLR-11 rocket engine ignited with hellfire, unleashing 6,000 pounds of explosive thrust that yanked him with unimaginably sudden force into the back of his seat. He was now in control of the tiny craft as it shrieked past 741mph, ripping a hole in the firmament another 20,000 feet up. And faster than you can say BOOM!,Yeager saw the needle on one critical dial swing past Mach 1 (an eponymous term coined for physicist Ernst Mach) indicating that he had overtaken the sound of his own aircraft. From now on an attacking plane would be long gone before the racket it made gave it away. Defenders could be dispatched without ever having heard it coming, never to hear it going.

The brutal buffeting of the X-1 caused by aerodynamic turbulence subsided. Supersonic shock waves flowed over and past the airframe, left in its wake. As Yeager recalled, “The faster I got, the smoother the ride.” He reveled in the triumphant roar of his rockets as he continued to streak through the firmament. But the officers, engineers, and flight crew on the ground were roundly startled before jubilation sank in. They heard something Yeager could not. It took a few beats to realize what what it was, what had just happened, confirmed by radar telemetry. They were the first beings ever to hear the ear-splitting CRACK! CRACK!joined by a window-rattling pressure wave we now recognize as a sonic boom. Two-and-a-half minutes later little rocket plane flamed out, having spent all its fuel. Yeager glided the now silent X-1 to a “dead stick” landing on the dry lakebed adjacent to Muroc Army Air Field (later renamed Edwards Air Force Base).

Tom Wolfe, with spellbinding prose in The Right Stuff, described Yeager’s euphoria at being quite literally on top of the world, for having achieved this aviation milestone:

The X-1 had gone through “the sonic wall” without so much as a bump. As the speed topped out at Mach 1.05, Yeager had the sensation of shooting straight through the top of the sky. The sky turned a deep purple and all at once the stars and the moon came out — the sun shone at the same time. … He was simply looking out into space. … He was master of the sky. His was a king’s solitude, unique and inviolate, above the dome of the world. It would take him seven minutes to glide back down and land at Muroc. He spent the time doing victory rolls and wing-over-wing aerobatics while Rogers [dry] Lake and the High Sierras spun around below.

Few had predicted such a stunning success. No one had known for sure what would happen to an aircraft or its pilot as they approached Mach 1, or even if they could get close to that speed. Experts had voiced misgivings, like the early train-travel pundits who predicted suffocation. Some had feared that the “sound barrier” was unattainable by anything less solid, or more lifeless, than a rifle bullet or an artillery round, and that its encounter by a piloted aircraft was tantamount to flying into a physical obstruction that would tear it to pieces. With all of the unknowns and nay-saying, just the attempt itself was a testament to Yeager’s optimism, skill, and courage. He told me, “It’s [a test pilot’s] duty to fly the airplane. If you get killed in it, you don’t know about it anyway. So why worry?” Yet, he almost blew his big chance.

A two-horsepower romp on terra firma, two days before his historic flight, nearly scrubbed Yeager from the mission. He was galloping across the open range, racing neck-and-neck with the flesh-and-blood Glamorous Glennis, his wife. They were headed back to Pancho’s Happy Bottom Riding Club from an after-dinner ride on a Sunday night. It had gotten dark. The Yeagers’ horses came up too fast on the corral to see that someone had closed the gate. Glennis’s horse veered away in time but Chuck’s horse, having taken the lead on the home stretch, hit the fence. The animal was unhurt but Chuck was thrown from his saddle. He broke two ribs.

Pancho’s was a dude ranch, an isolated retreat in the California high desert. Past its prime, it had once been the place to go for city slickers to find their inner buckaroo; just a few hours drive from Hollywood. Pancho Barnes, the proprietor, was a Calamity Jane-type who dumped four well-to-do husbands, ran guns for Mexican revolutionaries (hence the Pancho moniker), cursed anyone who looked at her the wrong way with unladylike language, and, as an amateur pilot, flew the barnstorming circuit and broke Amelia Earhart’s airspeed record in 1930. The word motel was still catching on in the 1940s; and, aside from the corral adjacent to the parking lot, Pancho’s was more of a “motor court.” But it had a landing strip, too. (She used to call her joint the Fly Inn.) It also boasted a swimming pool, a restaurant, and, of course, a bar. The bar was a popular watering hole for pilots stationed at the nearby airbase. Pancho’s was a tip of the cowboy hat to the romance of Wild West saloons, but one that catered to gunslingers of another sort: flyboys, instead of cowboys, who strapped on wings bristling with high-caliber machine cannons instead of six shooters. It had become an unsolicited honor for test pilots to have their likenesses hung willy-nilly on the walls. It meant they were dead. Test pilots had a 25% chance of dying before their 30th birthday. All the action was at 12 o’clock high, not high noon over a dust-blown street in a frontier town like Muroc.

Yeager knew he’d be grounded if his CO discovered his mishap, so he surreptitiously visited an off-base doctor and had his upper torso wrapped up tight like a mummy. He could hide the bandages under his flight suit. But he had another problem. Partially immobilized and in pain, he would be unable to twist his body and reach over to secure the hatch once he shoehorned himself inside the cramped cockpit. In cahoots with an Air Force flight engineer, he jerry-rigged a low-tech solution for one of the most high-tech experiments of the twentieth century: a sawed-off wooden broom handle was smuggled aboard the X-1 to use as a lever, to batten down the hatch.

Incidentally, Yeager made a cameo appearance in the movie version of “The Right Stuff.” He played a bartender at Pancho’s and exchanged lines with his thespian doppelgänger. After hours, when shooting on location in San Francisco, the cast and crew hung out at a bar in San Francisco’s North Beach called Tosca. Yeager himself could be found in the back room playing pool with director Phillip Kaufman. A few brawls broke out amongst the extras, according to a “Wired” magazine interview with Sam Shepard. Tosca became my favorite hangout when I moved to the Bay Area in 1987. A scale model of the X-1 pointed toward the heavens from a plinth standing amongst the bottles behind the bar.

PART TWO

“It’s not the fall that kills you, son, it’s the sudden stop.”

General Yeager and I wrapped up our photoshoot in Barstow. For my benefit, he’d already revisited his existential duel with the sound barrier. I asked if he was ready to wow me once again; this time to tell me about his harrowing bailout, twenty years earlier in 1963, from a rocket-assisted Lockheed NF-104A Starfighter. It was one of only three of these combat jets modified for aerospace testing by bolting on a rocket engine over its tailpipe, Buck Rogers style. For a second time, I was transfixed by the general’s steely blue eyes, notorious for their raptor-like acuity. In aerial combat his 20/10 vision helped him see the enemy before they saw him. What he was about to tell me, just like the flight of the X-1, happened close to where we stood that day. You could crane your neck straight up to see where the drama played out.

Yeager didn’t have to go up that cold December day. He was a full-bird colonel who ran the Aerospace Research Pilots School, the test-pilot program at Edwards AFB. He was the CO. The pilots under his command called it Yeager’s Charm School. But he wanted a firsthand feel for the hot-rod 104 his men were flying and for the nut-case maneuver he had them practice called a “zoom climb.” Vietnam aside, they were fighting a Cold War and competing in a Space Race with the Soviet Union. He and his pilots were “pushing the outside of the envelope,” wringing out the limits of endurance for man and machine. Test pilots coined that expression. Yeager was also personally impatient to break an altitude record held by some “Rooskie.”

Taking off from Edwards AFB, Yeager went “balls to the wall” on his ascent, accelerating his J79-GE-19 turbojet engine at full throttle. Edging up to the normal ceiling of an F-104 at 50,000 feet, he anticipated that the engine would shut itself down once he got there because, at that altitude, there’s not enough oxygen for jet fuel to burn. Passing through 40,000 feet he triggered his afterburner giving him an extra jolt for a total of 17,900 pounds of thrust, wringing out every inch of sky he could. That extra shove shot him up to 60,000 feet where he lit the Rocketdyne AR2–3 booster packing its own supply of oxidized propellant (90% hydrogen peroxide mixed with JP4 jet fuel). The extra G-forces slammed him into his seat and pulled the Starfighter up into a steep 70º angle of attack, trading the kinetic energy of relative horizontal speed for altitude, climbing faster than 1,630mph (Mach 2.2) past 108,700 feet. Having exhausted every last ounce of propellant to get there, the rocket engine, too, just stopped like a sudden cardiac arrest; and like the organs of a dying patient shutting down, the hydraulic system was next to go, leaving Yeager with no flight controls: no ailerons, no flaps, no rudder — no steering. Ballistic momentum alone carried the Starfighter toward the apex of the zoom climb, creeping closer to the edge of space, inky blue and getting inkier, then through an arc of weightlessness twenty-one miles above the earth like a high fly ball about to come down.

Yeager was no longer actually flying. Even if he had power, the stubby wings of the F-104 had no purchase on the few molecules of air that high up. After a brief hiatus from gravity his plane now had the aerodynamic characteristics of an anvil. He was dead weight in the sky, still pointing up but already falling down — tail first. Pressurization was gone, too; no power, no air in the airplane. To breathe, Yeager now relied on a full-body, hermetically-sealed flight suit and helmet — an early experimental spacesuit. But he anticipated all of this. It’s what the zoom climb was all about. That’s why he was counting on — and knew his life depended on — eight small nozzles in the Starfighter’s nose and wingtips to squirt short bursts of hydrogen-peroxide, the precursors of spaceship thrusters, to pitch the nose down. That matters because, if the pointy end is aimed at the ground while the engine is gasping for breath in a steep dive, it eventually encounters denser air that flows through intake ducts on the forward sides of the fuselage, like nostrils, and reaches a turbine. Fast-flowing air causes the turbine to spin, “windmilling” the engine. It works like push-starting a car, or a mechanical ventilator pumping air into the lungs of someone who’s stopped breathing. This technique generates enough hydraulic pressure to make the flight controls operational and, at the same time, the jet engine can gulp enough O2 to reignite the fuel and restart. The problem was, the engine cut out just a hair’s breadth shy of the altitude Yeager needed for those little H2O2 thrusters to work. He couldn’t get the nose down.

Training eclipses terror. Falling bass-ackward out of the sky, soundlessly but for the sibilance of his breath inside his helmet, he was profoundly alone; an insignificant mote engulfed by a featureless expanse, cold and dimensionless, bereft of any visual reference or sense of scale. He could not see the ground. Continuing to fall relentlessly for tens of thousands of feet more, Yeager mustered his wits to join in battle against a machine conspiring with gravity to kill him, methodically running through every trick in the book. He helped write the book. He would write a new chapter if he survived. He knew that that was his job as a test pilot. “It’s not the fall that kills you, son,” Yeager told me, “it’s the sudden stop.”

Cleverly, he deployed a drogue parachute that, under ordinary circumstances, pops out of the Starfighter’s tail to brake its speed once landed on a runway. Catching air and using it for leverage, this improvised tactic pulled the tail up, alright, and brought the nose down. He was ready to pick up speed in a dive and restart the engine. But when he jettisoned the drogue, the nose heaved itself back up again. It had to be the tail flaps! Yeager quickly realized, to his dismay, that these flaps, these aerodynamic wing stabilizers, were just doing their job, now that he had dropped into denser air. But they were stuck in position for the zoom climb, to fly up; stuck because there was no hydraulic power. To make matters worse, as Sir Isaac Newton would have been pleased to explain, the instant release of energy, when the drogue let go, whipped the plane into a “flat spin” at 8,500 feet, still plummeting but whirling like a Frisbee. Centrifugal force made it hard for Yeager to stay conscious, let alone keep his eyes on the altimeter; its needle rotating rapidly counterclockwise around the dial. But he could not afford to let his eyes wander. Focus! If he experienced vertigo or passed out from too many Gs, his stainless steel and titanium cocoon would become a coffin. Well, not even that. It would disintegrate, leaving him to look like a roast pig on a spit. He knew instinctually that terminal velocity left him about thirty seconds to impact, before he “bought the farm.” Splat.

Yeager had bailed out twice before. The first time he was States-side, before deploying to wartime Europe, when an experimental propeller failed on a training mission in a Bell Aircraft P-39 Aeracobra. The second time was when he got shot down over France in his first P-51. In those days a pilot tried to turn his airplane upside down so he could fall out, hoping not to get sliced by the tail rudder or diced by the spinning prop. Generally, though, he had to muscle his way out of a piston-pounding, gasoline-filled virtual bomb, likely shot to hell with holes and falling no matter which way it was turned, jump for his life, and stay conscious long enough to pull a ripcord. Twenty years on, no pilot wearing a prototype spacesuit had ever been blasted out of a jet, strapped like a monkey to a rocket-powered ejection seat. No time to think. At 5,000 feet, with the seconds ticking down and the ground rushing up, Yeager punched out.

Instantly, a pyrotechnic device blew the plexiglass canopy off the pinwheeling Starfighter, and Yeager, tucked into his Flash Gordon version of La-Z-Boy lounge chair, was catapulted into the sky like a bat out of hell with its tail on fire. The plane was falling at 100mph and the ejection seat shot him up, also at 100mph. Despite the meteoric expulsion, it gave Yeager a visual sensation of sitting in place while the airplane simply fell off — of him.

At 1,400 feet another charge fired automatically, separating Yeager from the ejection seat and deploying a “drag chute” from the harness on his back. This smaller parachute was designed to slow an escapee’s descent, just enough to avoid a too-violent opposition to the impetus of speed that might otherwise snap his spine while, in its wake, it pulled out the main, life-saving canopy. And for one implausibly long moment before gravity reasserted itself at the crest of their trajectory, like Wile E. Coyote sprinting past a precipice before looking down, the defunct ejection seat seemed to hang in the air next to Yeager, whose gaze was fixed on its exposed rocket nozzle. Turned sideways, now facing him, it was slathered with the viscous, bubbling-red-hot residue of propellant. Too close! But, again, no time to think. Within this same elastic Einstein-ian blink of time it came closer still, drifting into the lines of his drag chute, entangling, burning. Then whoosh. The gigantic main parachute streamed out, billowed open, and—THWAP!— caught air, instantly jerking Yeager up relative to the fiery apparatus in free fall beside him, and —WHUMP! — he caromed off its butt end. The collision shattered his helmet visor and cut a gash above his left eye that pooled with blood. Incandescent goop oozed inside his helmet and down his neck. Yeager was now drifting down like a snowflake while enduring flames that licked inside his helmet, fed by 100% pure oxygen escaping from his pressure suit — “It ignited like a blowtorch,” the general said. He was suffocating in the acrid smoke that wouldn’t clear his helmet. With great effort, using a gloved hand that suffered further burns, he managed to smash and pull on what was left of his visor to let the smoke out. Bloodied, sickened by the smell of melting rubber and plastic and his own burning flesh, Yeager screamed.

Still conscious, he landed on his feet and wrenched the helmet off his head, painfully, as his parachute fluttered down behind him. From the zenith of his climb, the entire episode lasted four minutes. Adrenaline addled, Yeager ambled away from the burning pyre that had once been a USAF jet fighter. It won the race to the bottom. He must have looked like a blood-soaked zombie in a spacesuit, carrying his crispy helmet stoically in the crook of his arm as he approached a rescue helicopter that arrived in minutes with a flight surgeon. The upshot was good telemetry for the Air Force and NASA, some anecdotal tactical recommendations, a one-and-a-half-million-dollar crater in the desert floor, and a wicked scar on Yeager’s neck. In short order, he was surfing the clouds above Edwards again. By 1966 he was back in command of a combat wing flying missions over Vietnam.

Weeks later, I offered up two prints of the portrait we made, and asked him to inscribe one for me. He wrote, Tom, you sure know how to show the feeling a guy has for his airplane. I had posed him (standing on a step-stool out of frame) fondling the nosecone of Glamorous Glennis. A fighter pilot’s ribald sense of humor might take that for a double entendre.

Sixty-five years — to the day — after he first demolished the idea of a sound barrier, Yeager climbed into the cockpit of a McDonnell-Douglas F-15 Eagle at Nellis AFB in Nevada and did it again at age 89, just for shits and giggles. He’s 95 years young today, living in the Sierra Nevada foothills and, I’m sure, always looking up into the wild blue yonder.

Tom Zimberoff is an accomplished commercial photographer, author, and photojournalist whose photographs have appeared on the covers of Time, Fortune, Money, People, and numerous other magazines.