The Beatles, Palazzo Pitti, and a Case of a Wrong Attribution

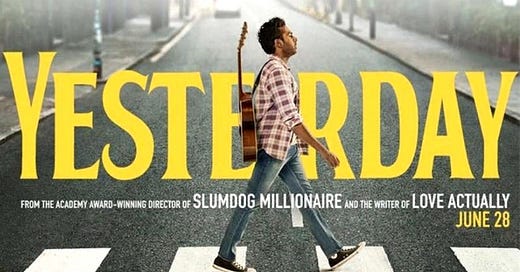

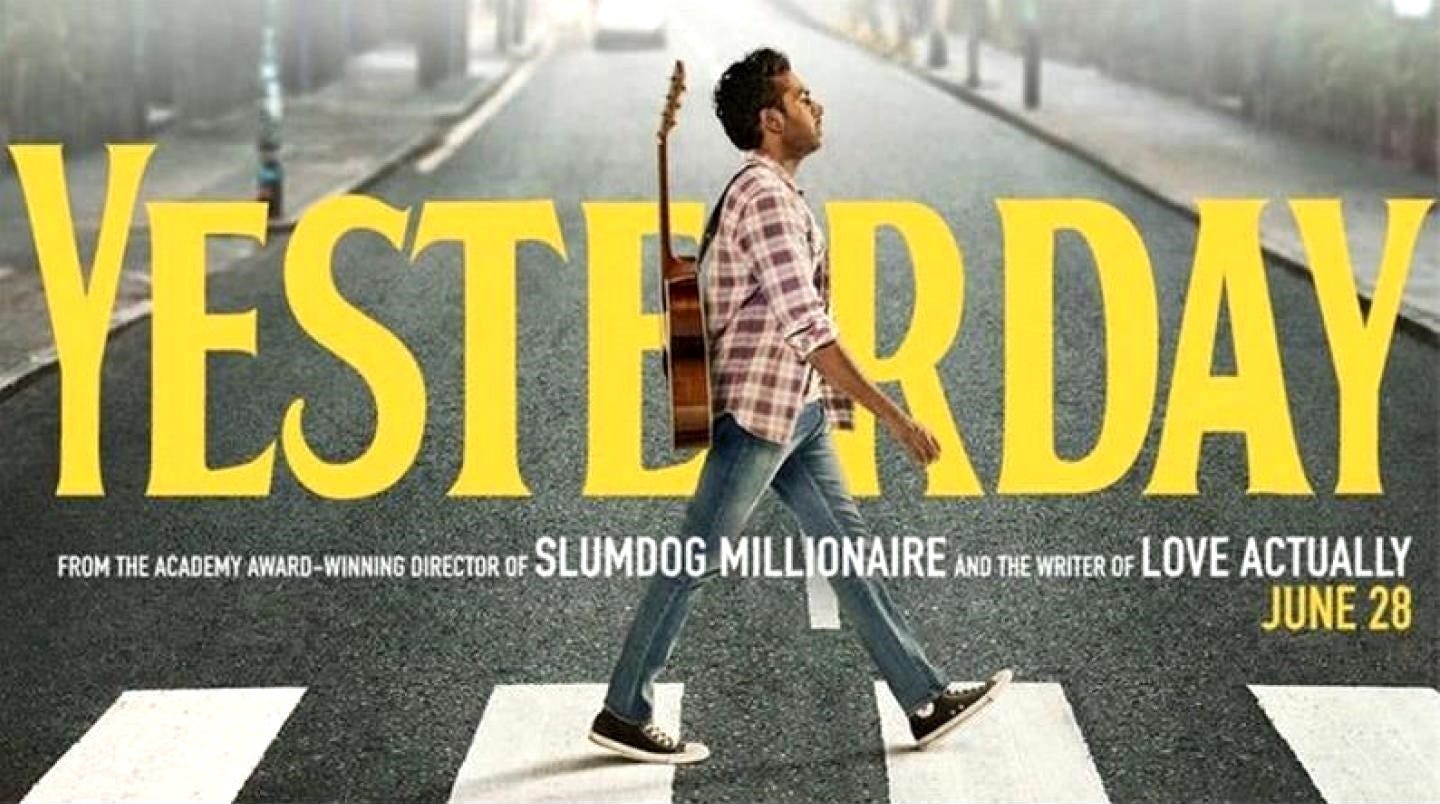

A non-spoiling non-review of Yesterday with a detour into Renaissance sculpture

By Ray N. Kuili

Yesterday I went to see Yesterday.

Iam probably not the only one to start an article about that movie with these words. However, I’m fairly certain that no one else is going to write about a Medici’s famous residence after that opener. The connection between these two rather distinct subjects exists, likely, only in my mind. But first things first. This article is spoiler-free, but it does mention the movie’s premise and one scene, both of which are in the trailer. And while it talks about the movie, it is not a review.

I went to see Yesterday with high expectations and exited the theater disappointed. If anything, the movie felt like a lost opportunity to tell a unique story based on a unique premise involving a unique band. What I saw was a fairly mediocre film with a predictable plot, mildly annoying visual effects, and yes, many great songs. It had its moments and overall was enjoyable, but the enjoyment was mostly rooted in the well-executed opening sequence, followed by anticipation of interesting plot twists, which, unfortunately, never materialized. If you like the Fab Four, it is still a movie worth watching, just not with the kind of expectations I had based on the trailer.

However, there was one scene in the movie that felt surprisingly powerful and struck a Fadd9 chord for me (do let me know if you get the reference). Which brings me to Palazzo Pitti. Some years ago, I happened to spend a day in Florence and had a foolish objective to see as many of its treasures as possible. To put this into perspective, I’m hardly an art aficionado. When it comes to sculpture, paintings, and architecture, I’m the equivalent of a guy who can sip a glass of cheap wine and enjoy it much more than a fine expensive product from a distinguished winery (actually, not the equivalent — I am that guy). I like what I like, and I don’t care for labels, positioning, framing, and other means used to persuade me that I should like something more than my own taste, however unsophisticated, suggests.

So when on that day in Florence I ended up in Palazzo Pitti, I was not looking for any specific names or works of art. In fact, I couldn’t name any of the works of art located in the place. I just explored one room after another, trying to make the most of it. But Palazzo Pitti is a big building, which has a lot of artwork. As in, a lot. And, as if this wasn’t enough, I was there after a visit to the Uffizi and shortly before the palace was about to close. As a result, a walk through the famous Palatine Gallery slowly turned into a blur of paintings and sculptures.

The Palatine Gallery

Magnificent works of art, each with a rich history, and dozens of people admiring them, all blended into one painting stretched over lavishly decorated walls. Countless sculptures created by true masters, some dating back to the Roman Empire, began to look as indistinguishable as mannequins in a department store (actually, less distinguishable due to the lack of colorful clothes). It was an hour’s walk through a place that should have been explored at least for a half a day.

And then I saw the statue.

It was located in the middle of a crowded room, among other — much bigger — sculptures. It neither had a sign in front of it nor was it emphasized in any other way. It clearly hadn’t been deemed important enough even to mention the name of the sculptor, as there was only a small tag with a long catalogue number. People were walking by it without stopping, heading for one of the bigger pieces. But there was something in that sculpture that made me stop.

It was a statue of a boy, who, in turn, was sculpting the head of a fawn. The boy was concentrated on the task, his small hand raising a hammer. And he looked alive. That face was not the face of a marble statue — it was the face of a real boy, who by means of some magic, had turned into marble. His intent gaze was not like the unseeing stare of statues around him. His right hand was perpetually frozen in real motion, ready to complete the movement and strike the chisel with his small hammer. And the partially finished face of the fawn looking back at its creator only amplified the striking aliveness of the boy’s face.

I remember standing there and wondering why this statue was not the most famous work of art in the room — or in the entire palace. It could be the work of some unknown genius or, more likely, the work of someone whose name was so obscure it hadn’t even justified a plate in front of the statue. Then I headed to the wall with dozens of small printed labels, corresponding to all artworks in the room. That was before the days of smartphone snapshots and image search, so leaving the room without finding out the name of the sculptor meant leaving without learning it any time soon, if ever. It also meant leaving the museum without seeing the rest of it, because it was closing soon. But I didn’t care. I wanted to know the little-known name of the little-known creator of that wonder.

Fifteen minutes later I found it — a small plate with a number matching the statue’s tag. There was no English translation, but I didn’t need one. Among several lines of Italian words stood one word I knew without a translator: Michelangelo.

I went back to the statue and traded seeing another room or two for a few more minutes in its company. It was no longer a mystery. The only mystery was why the curators of Palazzo Pitti had decided to give so little recognition to this amazing work of one of the most famous sculptors in history. But it didn’t matter. The statue was there, whether decorated with big signs or not.

For years, that small sculpture remained my example of how true art makes an impact regardless of the fame of its creator — and of how a work of a genius can be recognized in any setting even by someone who knows very little about the history of art. So when a scene from Yesterday (to which I will come in a moment) reminded me of that statue, I knew that even though I didn’t want to write a review, there was a related story to tell. What I didn’t know was that I was about to encounter a plot twist of the sort I had been looking for in the movie.

Typically, I write the text of articles before adding any visual elements. However, Medium’s clean editor makes it very tempting to insert images as you go and see the text evolve along with the right visuals. Finding a still from the movie was easy. Locating the right picture of Palazzo Pitti was even easier. But then I encountered a minor unexpected problem: no search query would point to a statue of a boy by Michelangelo in Palazzo Pitti. In fact, no search query would say anything about any Michelangelo’s work in Pitti’s galleries.

The only suggestions Google had to offer were the statue of David (located in

Galleria dell’Accademia, quite a few blocks away) and directions to a bus from Palazzo Pitti to Piazzale Michelangelo. I started feeling a bit like Yesterday’s protagonist Jack Malik when he was looking for any mention of The Beatles after an event that wiped them from history.

The statue existed! I saw it myself! And Michelangelo’s name was on that plate. Even if they moved the statue to a different location, wouldn’t at least some mention of it remain online? Or did I mix everything up and the piece of art wasn’t in Florence?

However, after a couple of attempts, the lost statue was found. It showed up in “Palazzo Pitti Michelangelo faun” query. I looked at it as if it were my own long-lost object. It hadn’t changed much since my visit. The pictures weren’t doing justice to the boy’s live facial expression, but it was undoubtfully that statue. So why in the world would they not even mention the name of its sculptor?

As it turned out, they did. Only it wasn’t Michelangelo. It was a sculpture by a man named Cesare Zocchi, aptly named Young Michelangelo Chisels the Faun’s Head. I had been right after all — Michelangelo’s name was on that plate. Except it wasn’t the name of the sculptor. It was the name of the sculpture. There was an interesting story behind it.

Faun’s Head is considered the first distinctive sculpture by Michelangelo. He made it when he was 15 and that sculpture played a critical role in securing him the patronage of Lorenzo de’ Medici at such a young age. Medici happened to see Michelangelo work on that sculpture, which was supposed to be an exercise in copying an antique original. Michelangelo, being the genius he was, decided to customize the original, which had its mouth closed, and made his copy with a wide grinning mouth, making the face much more realistic. Impressed, Medici complimented his work but told him that an old fawn was unlikely to have perfect teeth.

According to some sources, Michelangelo immediately took a chisel, and with a few precise strikes broke the fawn’s teeth. According to others, he brought the faun’s head to Medic next day, with an artfully chiseled hole instead of one tooth. In either case, Medici was so impressed with the young sculptor that he offered his patronage. Had it not been for that encounter, Michelangelo’s entire life and, along with it, a big chunk of Western art, could have turned out very differently. The sculpture was lost, but the story remained, and three hundred years later inspired Cesare Zocchi to make a statue of the young Michelangelo working on his first masterpiece. (The authorship is actually more complicated than that since some sources attribute the sculpture to Cesare’s cousin Emilio Zocci.).

And then, another hundred and fifty years later, it made an unforgettable impression on me.

So how is this all related to Yesterday? It is related to the movie’s pivotal moment, where Jack learns that The Beatles have been erased from history and everyone’s memory. He discovers that fact after he sings Yesterday to a few friends. Having never heard the no-longer-most-covered-song-in-history, they assume he wrote it. And their reaction to it, for me, is the best moment of the entire movie. The reaction doesn’t last long — they know the song was written by a struggling amateur (and soon after expressing their astonishment comes the “Of course, this is not Coldplay” line). But for a brief moment, they show what the impact of powerful art looks like, regardless of the name of the artist.

And that’s why I still consider that little statue in Palazzo Pitti one of the best sculptures in the world. Even though now I know it was not made by Michelangelo.